Common sense is science exactly in so far as it fulfils the ideal of common sense; that is, sees facts as they are, or, at any rate, without the distortion of prejudice, and reasons from them in accordance with the dictates of sound judgement. And science is simply common sense at its best; that is, rigidly accurate in observation, and merciless to fallacy in logic. ― T. H. Huxley, 1896. 1 The Crayfish: An Introduction to the Study of Zoology, Thomas Henry Huxley. At Gutenberg

Huxley's statement is both encouraging and demanding: science is not mysterious or remote, so it is open to all, but the scientific investigator must perform at the highest level of honesty and impartiality.

A particular characteristic of science education is that key conceptual elements are identified by the name of the scientist who devised each one. These select figures are held in great respect, and have become true immortals:

Nature and Nature's laws lay hid in night: God said, Let Newton be! and all was light. ― Alexander Pope

This is not just the imagery of a poet, it is a part of our science education. This is in stark contrast with Huxley's basic principles: here, idolatry takes the place of observation and judgement.

There is a lasting disagreement about who held the light that shone on Nature's laws. Concern about the misinformation of generations of students was eloquently expressed by Robert Weinstock, in Problem in two unknowns: Robert Hooke and a worm in Newton’s apple published in The Physics Teacher, 1992.

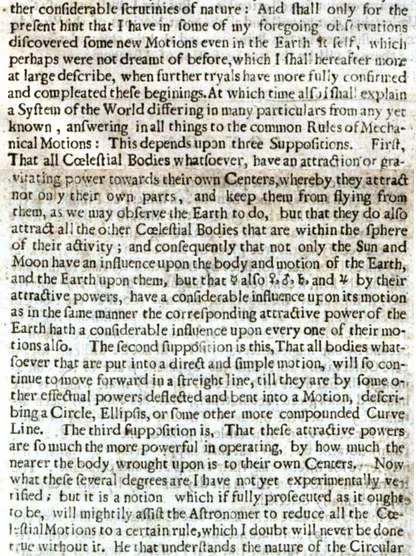

The concern is easily illustrated by the celebrated passage from An Attempt to Prove the Motion of the Earth from Observation in Hooke's Cutlerian Lectures, 1674.

I shall explain a system of the world, differing in many particulars from any yet known, answering in all things to the common rules of mechanical motions. This depends upon 3 suppositions; first, that all celestial bodies have an attractive of gravitating power towards their own centres, whereby they attract not only their own parts, and keep them from flying from them, as we observe the Earth to do, but that they do also attract all the other celestial bodies that are within the sphere of their activity, ... The second supposition is this, that all bodies, that are put into direct and simple motion will continue to move forwards in a straight line, until they are by some other effectual powers deflected and bent into a motion describing a circle, ellipsis, or some other uncompounded curve line. The third supposition is, that these attractive powers are ‘so much the more powerful in operating, by how much nearer the body wrought upon is to their own centres

Anyone who has learned Newton's laws of motion will recognise the first of them in the earlier passage by Hooke. Further, Hooke's System of the World declares the unification of terrestrial and celestial mechanics for which Newton has been given the credit. The issue of Hooke's contribution to celestial mechanics remains in contention thirty years on from Weinstock's paper.

The four relevant Wikipedia pages (Principia, de Motu, Universal gravitation, Hooke) dismiss Hooke's work, with the same quote (from a mathematician):

"One must not think that this idea ... of Hooke diminishes Newton's glory", Clairaut wrote; "The example of Hooke" serves "to show what a distance there is between a truth that is glimpsed and a truth that is demonstrated".

The Wikipedia content is based on numerous sources, but in the most significant case the source does not actually substantiate the content.

It seems that for all the rehabilitation of Hooke's reputation, he is being given only a small part of the credit for celestial mechanics. A particularly vigorous assertion of a contrary view appeared in 2017 (Gribbin and Gribbin 2 Out of the Shadow of a Giant: Hooke, Halley & the Birth of Science. John Gribbin and Mary Gribbin. 318 pp. Yale U. P., New Haven, CT, 2017. ):

Comparing those almost contemporaneous accounts, the modern reader is left in no doubt who was the forward-looking scientist with great insight, and who was the backward-looking mystic with a head filled with magical mumbo jumbo.

Hooke was a great scientist, who came up with the first scientific world-view; Newton was a great mathematician, who put Hooke’s world-view on a secure mathematical foundation, and then claimed credit for the whole thing himself.

How can we sum up the relative achievements of Hooke, Halley and Newton, and their contribution to the scientific revolution? ... None of them deserves to be remembered in the shadow of any of the others, but if push came to shove, we would certainly place Hooke ‘first among equals’.This vigour has been countered by a distinguished historian of seventeenth century mechanics in his review 3 Michael Nauenberg, Review of: Out of the Shadow of a Giant: Hooke, Halley & the Birth of Science, American Journal of Physics 86, 79 (2018); DOI: 10.1119/1.5012509 of the Gribbins' book:

If one wants to avoid the irritation caused by such ridiculous comments and similar ones elsewhere in this book, it is better not to read it.

Why should these disagreements persist? However much the historians may agree that Hooke has been hard done by, and that his name should be credited alongside Newton in celestial mechanics, this has not been transmitted to the National Curriculum. Perhaps the reason is the great significance of the topic: it is regarded as the first Great Unification of physics, so the reputational stakes are high, and the feelings also. This cannot be the sole reason, however; the second Great Unification was James Clerk Maxwell's 19th century unification of electricity and magnetism, where the stakes are just as high, but the outcome is very different:

Faraday was an experimentalist who conveyed his ideas in clear and simple language. His mathematical abilities did not extend as far as trigonometry and were limited to the simplest algebra. Physicist and mathematician James Clerk Maxwell took the work of Faraday and others and summarised it in a set of equations which is accepted as the basis of all modern theories of electromagnetic phenomena. On Faraday's uses of lines of force, Maxwell wrote that they show Faraday "to have been in reality a mathematician of a very high order – one from whom the mathematicians of the future may derive valuable and fertile methods" (Wikipedia).

In this case there is no attempt to dismiss the earlier work as a mere glimpse of the truth, or to denigrate it in comparison with Maxwell's monumental achievements. Maxwell's generosity is in stark contrast with Newton's meanness. It would be a fine thing if we could achieve a similarly balanced view of the roles Hooke and Newton in the first Great Unification. This can only be justified on the basis of a detailed examination of the original evidence and sources. This is given in detail at Robert Hooke and celestial mechanics.

2 Out of the Shadow of a Giant: Hooke, Halley & the Birth of Science. John Gribbin and Mary Gribbin. 318 pp. Yale U. P., New Haven, CT, 2017.

3 Michael Nauenberg, Review of: Out of the Shadow of a Giant: Hooke, Halley & the Birth of Science, American Journal of Physics 86, 79 (2018); DOI: 10.1119/1.5012509