In 1992, Robert Weinstock published Problem in two unknowns: Robert Hooke and a worm in Newton’s apple in The Physics Teacher. It is an eloquent and accessible plea for recognition of Hooke's work. At that time there was a general lack of awareness of Hooke's life and work, beyond the law of spring which bears his name, and his controversy with Newton. Although awareness has risen since then, the division of opinion on his achievement continued. For example, Weinstock's paper was not mentioned in Isaac Newton, the Last Sorcerer by Michael White when the book appeared in 1997.

White introduces Hooke in a chapter on "Feuds", where his character is described in these terms

hot-headed and scheming...had already gained something of a reputation for making unsubstantiated claims... was looking for any opportunity to escalate the feud...Fond of intrigue and thriving on gossip...disguising his patronising manner with sugar-coated linguistic finery...Employing his lucky guesses with the skill of the practised self-publicist and driven by a hatred born of humiliation...he was the medieval alchemist to Newton’s empirical ‘scientist’

The partisan nature of this assassination is clear in view of the account of Hooke's life by Margaret 'Espinasse (Heinemann, 1956), which dispels the myths about Hooke's character which White is propagating. White does not mention the then standard 'Espinasse biography either. Views of Hooke and his work were firmly established in two camps.

In 2003 a conference was held at The Royal Society of London to mark the tercentenary of the death of Robert Hooke. Hooke's contribution to the development of celestial mechanics and the theory of gravitation received expert attention from specialists. My own paper Assessment of the Scientific Value of Hooke’s Work was presented at the London conference, and subsequently adapted it to form Chapter 6 of the conference book 1 Robert Hooke - Tercentennial Studies (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006) . The material is also presented here at How can we assess the scientific value of Hooke’s Work?. It argues that other assessments of Hooke's wider work on mechanics dismiss it generally as riddled with elementary errors, and conclude that none of his contributions could be of any value. It demonstrates that the authors of these assessments had themselves only an elementary understanding of the subjects that Hooke studied, and that the errors were not on Hooke's part.

Since the 2003 conference there have been several biographies of Hooke, and a flood of academic studies on him. Hooke is no longer the person whose main claim to fame is that he had disputes with Newton. The popular biographies by Stephen Inwood and Lisa Jardine have further debunked Michael White's attempted assassination of Hooke's character. This transformation is described by Robert D. Purrington, who in 2009 wrote "In any event, the last two decades have seen Robert Hooke rise from almost total obscurity to the point that he is nearly fashionable, something that would have been unimaginable not so very long ago" 2 Robert D. Purrington, The First Professional Scientist: Robert Hooke and the Royal Society of London, Science Networks, Historical Studies, Volume 39 2009 page xiii . There is a web site dedicated to Hooke, which is a cornucopia of resources. On the other hand, there is still another where Hooke is portrayed as a simple villain.

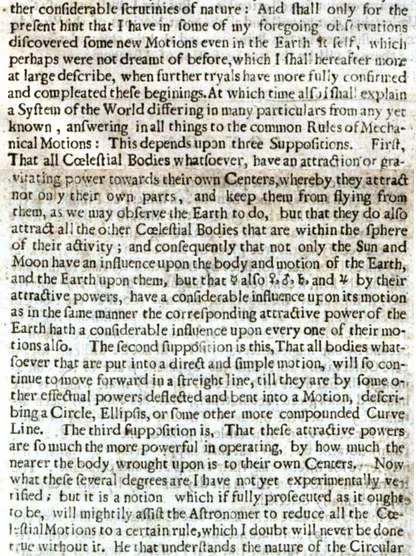

Hooke may have become almost fashionable, but Hooke's contribution to celestial mechanics has yet to be properly recognised. The 'Espinasse biography gives an introduction to his Micrographia and Cutlerian Lectures, but as far as his work on science and mechanics is concerned, she defers to Jacob Bronowski's view of Hooke as being "yesterday's man" 3 The Common Sense Of Science, Penguin, 1960, Jacob Bronowski, Chapter 3 Isaac Newton's model, esp.p34-5 . In this view, the future of mechanics lay in the mathematical analysis inaugurated by Newton. It appears that Bronowski was unaware of Hooke's System of the World when he made this assessment. Unsurprisingly, White's commentary on the System of the World dismisses Hooke's efforts as mere guesses.

More recent popular biographies convey that Hooke's contribution to celestial mechanics was insignificant: Inwood writes as though Newton had all the concepts he needed anyway 4 Stephen Inwood, The Man Who Knew Too Much: the strange inventive life of Robert Hooke, 1635-1703, Macmillan 2002, pages 293, 296, 297 , although the sources he cites do not support that view. Jardine (née Bronowski) retains the view that Hooke was "yesterday's man", and not a part of the mathematical breakthrough 5 Lisa Jardine The curious life of Robert Hooke : the man who measured London. London : HarperCollins, 2003, page 319 .

A balanced view of the roles Hooke and Newton requires both a consideration of the nature and value of their work, and a detailed examination of the original evidence and secondary sources. These are presented here at Celestial and at Glimpses.

The case of Robert Hooke is not exceptional. The conclusions of the above mentioned essay on the assessment of Hooke's work are that

A view arises from the present study that might be more widely applicable. Science appears as technology carried out with greater depth. Thus technology is first to achieve a dim understanding, and science is first to achieve a full one. Chronologically and causally, technology gets there first, and drives discovery forwards. Technology has to make do and mend, until science clarifies and organises. These strands remain distinguishable even in the close integration of the modern era. This view retains the need to defend resources for science to go deep, but does not support the notion of science for its own sake.

This view calls into question how physical science is presented, both to specialists and others. The laws of motion, for example, are learned right at the beginning of a physics course although historically they were not formulated until long after mechanical devices were being designed that were far too complex to be analysed by using them. Elementary science students are baffled and disheartened by the “laws first” textbook presentations and find it inimical to clear thinking and inspiration. It appears that the current syllabus is without pedagogical, conceptual or historical justification. It is still the common basis for the assessment of scientific value in historical studies.

These conclusions are developed and extended here at Clockwork, and in a set of web pages, summarised at Introduction. They present the nature of what we call science and technology, and how they are taught in four countries. The pages also look in detail at the history of perhaps the most important technical development in which the role of science is widely asserted: the advent of steam power.

1 Robert Hooke - Tercentennial Studies (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006)

2 Robert D. Purrington, The First Professional Scientist: Robert Hooke and the Royal Society of London, Science Networks, Historical Studies, Volume 39 2009 page xiii

3 The Common Sense Of Science, Penguin, 1960, Jacob Bronowski, Chapter 3 Isaac Newton's model, esp.p34-5

4 Stephen Inwood, The Man Who Knew Too Much: the strange inventive life of Robert Hooke, 1635-1703, Macmillan 2002, pages 293, 296, 297

5 Lisa Jardine The curious life of Robert Hooke : the man who measured London. London : HarperCollins, 2003, page 319